Guilt by Association

Trump administration uses immigration law to target Colorado attacker’s family

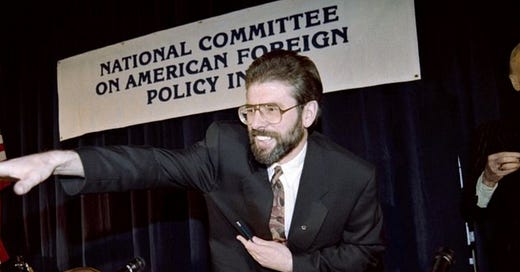

In his first speech as political leader of Sinn Fein, Gerry Adams left no doubt about his support for the Irish republican group’s militant wing. “Armed struggle is a necessary and morally correct form of resistance,” he said in 1983. As a high-ranking official in an organization with a long, bloody history in pursuit of Irish independence, Adams was barred from entering the United States. And yet in 1994 he stood in the center of Manhattan speaking publicly inside a hotel ballroom. Despite being the leader of an organization described by the United States as terrorist, U.S. officials nonetheless let him into the United States. It wouldn’t be the only time that he was permitted to travel to the United States.

Three decades later, the United States government is adopting the opposite approach towards the wife and children of Mohamed Soliman. An Egyptian citizen who overstayed his tourist visa, Soliman is currently detained in Colorado facing terrorism charges after attacking Jews in Boulder. He appears to have lived with his wife and five children in Colorado Springs. News reports suggest that he has an asylum application pending.

The Trump administration has also detained Soliman’s wife, Hayam El Gamal, and their children. Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem explained on social media that the family members are in ICE’s custody. State Department officials reportedly said that the administration revoked the Soliman family’s visas after Sunday’s attack. The White House later added that they “could be deported by tonight.”

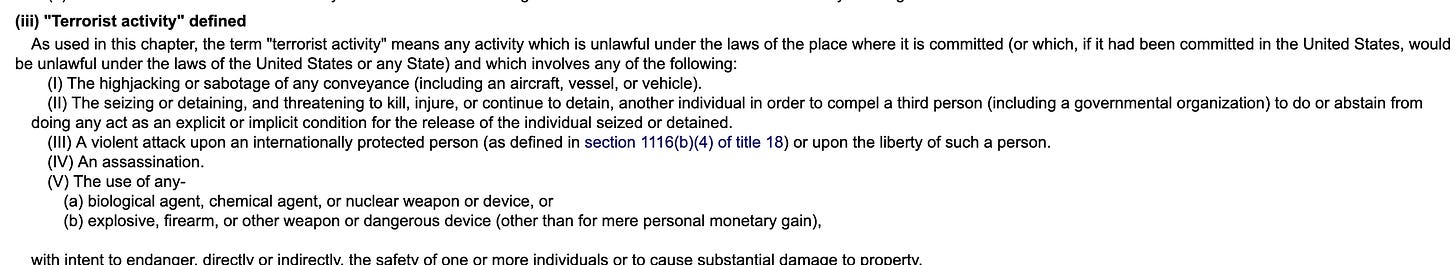

If convicted of any number of offenses, Soliman will be deportable despite the pending asylum application. The Immigration and Nationality Act permits State Department officials to deny a visa to people involved with terrorism. Having used some type of flammable liquid to burn people, Soliman’s conduct almost certainly meets the definition of terrorism used in immigration law.

Targeting Gamal and the children under immigration law’s terrorism provisions is another matter. Congress has authorized immigration officials to exclude from the United States “the spouse or child” of a person who engages in terrorism activity within the previous five years. It’s too early to know whether Soliman’s relatives knew or should reasonably have known about the horrific actions he planned. The children range in age from four to seventeen years. If Soliman’s relatives weren’t aware of his plans, they are not subject to the terrorism basis of exclusion.

In addition, Gamal and the children are not excludable because they have already been admitted into the United States. Even if Soliman’s relatives entered the United States on tourist visas and stayed past the short duration of their permitted visit, as Soliman reportedly did, they are not excludable from the United States because they have already been admitted into the United States. Immigration law defines admission as entry after inspection and authorization by an immigration official. Everyone who arrives at an international airport and is permitted to enter by a Customs and Border Protection officer satisfies this definition.

The comparable basis for deporting people who engage in terrorism also probably doesn’t apply to Soliman or his relatives if they have been admitted because the deportation basis only applies to someone “who is described in” the inadmissibility provision. Since anyone who has been admitted is not subject to inadmissibility, they likely can’t be described in the inadmissibility section.

Strikingly, the Trump administration is pushing immigration law to new terrain by targeting people merely for their association with someone who has engaged in violence. I haven’t found a single instance in which immigration authorities tapped the family provisions of immigration law’s terrorism basis of inadmissibility or deportation. In the few instances in which federal officials tapped the anti-terrorism parts of immigration law, they went after people for their own conduct. Going after Soliman’s wife and children brings guilt-by-association squarely into the mainstream of U.S. immigration law.

There is another reason to be doubtful about the legality of the Trump administration’s decision to go after Soliman’s family. The State Department has said that it has revoked the relatives’ visas. Federal officials certainly have a lot of discretion when deciding whether to grant someone a visa. Once issued, it’s another thing entirely to take away a visa. As courts have made clear in numerous lawsuits involving the administration’s attempts to revoke student visas, federal law imposes tight restrictions on the government’s power to revoke a visa that has been lawfully granted. So far, nothing suggests that any family member obtained their visa fraudulently. Plus, a visa is key to admission into the United States, but now that they are in the United States they are entitled to wait out the asylum application process.

Unless what is known about the family’s immigration history changes, DHS isn’t legally permitted to put the family members into expedited removal proceedings. A fast-track option for circumventing immigration courts, expedited removal only applies to people who either entered without a visa or through fraud. Neither appears to be the case here.

Federal officials are trying to do through immigration law what they can’t do through criminal law: punish people for something they didn’t do. How far they get will depend on how much judges are willing to allow guilt-by-association to result in detention and deportation. On Wednesday afternoon, a federal judge in Denver temporarily blocked DHS from deporting Gamal or the children.

By the time Gerry Adams entered a ballroom at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City to make his case for Irish independence directly to an audience in the United States, over 3,000 people had died in Northern Ireland in the previous 25 years. Yet Adams didn’t denounce violence. Decades later, he would credit the Clinton administration’s decision to let him visit New York City with boosting the peace process.

Immigration law is remarkably flexible, as Adams’ visit to the United States shows. But by targeting Soliman’s family through obscure sections of immigration law, Trump is using the law’s flexibility as a weapon rather than a valuable tool to promote greater understanding.