Rewriting citizenship

Trump executive order targets parents living legally in United States

As a college professor, I teach students from abroad almost every year. All of them are in the United States lawfully, often on a visa intended specifically for students, and many of them are married to people who they met in whatever place they called home before moving to the United States. Their children born in the United States would not be recognized as U.S. citizens if an executive order that President Trump signed on day one goes into effect. Part of Trump’s campaign promises, the order’s radical rewriting of more than 100 years of citizenship law is certain to face a long legal battle.

The president’s policy orders the State Department, Social Security Administration, and other federal government agencies to deny U.S. passports to people born on or after February 19, 2025, who can’t show that both their parents were either U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents at the time of the child’s birth. Anyone whose mother was in the United States unlawfully is barred from receiving a U.S. passport if the applicant’s father was neither a citizen nor permanent resident. The executive order also bars passports to anyone whose mother was in the United States lawfully on any of the dozens of temporary, non-immigrant visas that exist under immigration law if the applicant’s father was neither a citizen nor permanent resident.

Immigration officials regularly admit into the United States people on the kind of temporary visas that would trigger a passport denial. In 2023, there were 132 million instances of a person being admitted into the country on one of these visas. That was lower than any year during Trump’s first term except the Covid-impacted 2020.

Trump’s policy shift threatens to change how U.S. citizenship has been obtained since 1898. That year Wong Kim Ark, born in California to Chinese parents, won a legal fight to have the U.S. government recognize him as a U.S. citizen. Government lawyers argued to the Supreme Court that the United States had a longstanding history of barring Chinese citizens from entering the United States or obtaining citizenship through naturalization. No one could deny that they were correct. In 1882, Congress had enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act which accomplished the goal that its name suggested. Since Congress had clearly illustrated the national distaste for Chinese residents, surely birth in the United States couldn’t lead to U.S. citizenship, the government’s position added.

In a split decision, six justices of the Supreme Court disagreed. The “citizenship of the child followed that of the parent” in ancient Rome, but the United States inherited its legal tradition from the United Kingdom, the majority of justices explained. By the time that the colonies seceded from the king of England, citizenship was based on presence within the king’s domain. Only two exceptions existed then. One for the children of foreign ambassadors and the other for the children of invading troops.

The Court’s reasoning was simple. “The party must be born within a place where the sovereign is at the time in full possession and exercise of his power, and the party must also at his birth derive protection from, and consequently owe obedience or allegiance to, the sovereign, as such.” Following this rationale, the justices added indigenous people born to members of native tribes to the list of exceptions from the traditional rule of birthright citizenship. Decades later, Congress enacted a law granting citizenship at birth to indigenous people, but it has never extended this privilege to the children of ambassadors or invading forces.

Despite widespread animosity toward Chinese citizens, Wong Kim Ark’s parents were in the United States lawfully and they were neither ambassadors nor invading troops. Indeed, the constitutional amendment was broad enough that it “includes the children born within the territory of the United States of all other persons, of whatever race or color, domiciled within the United States.”

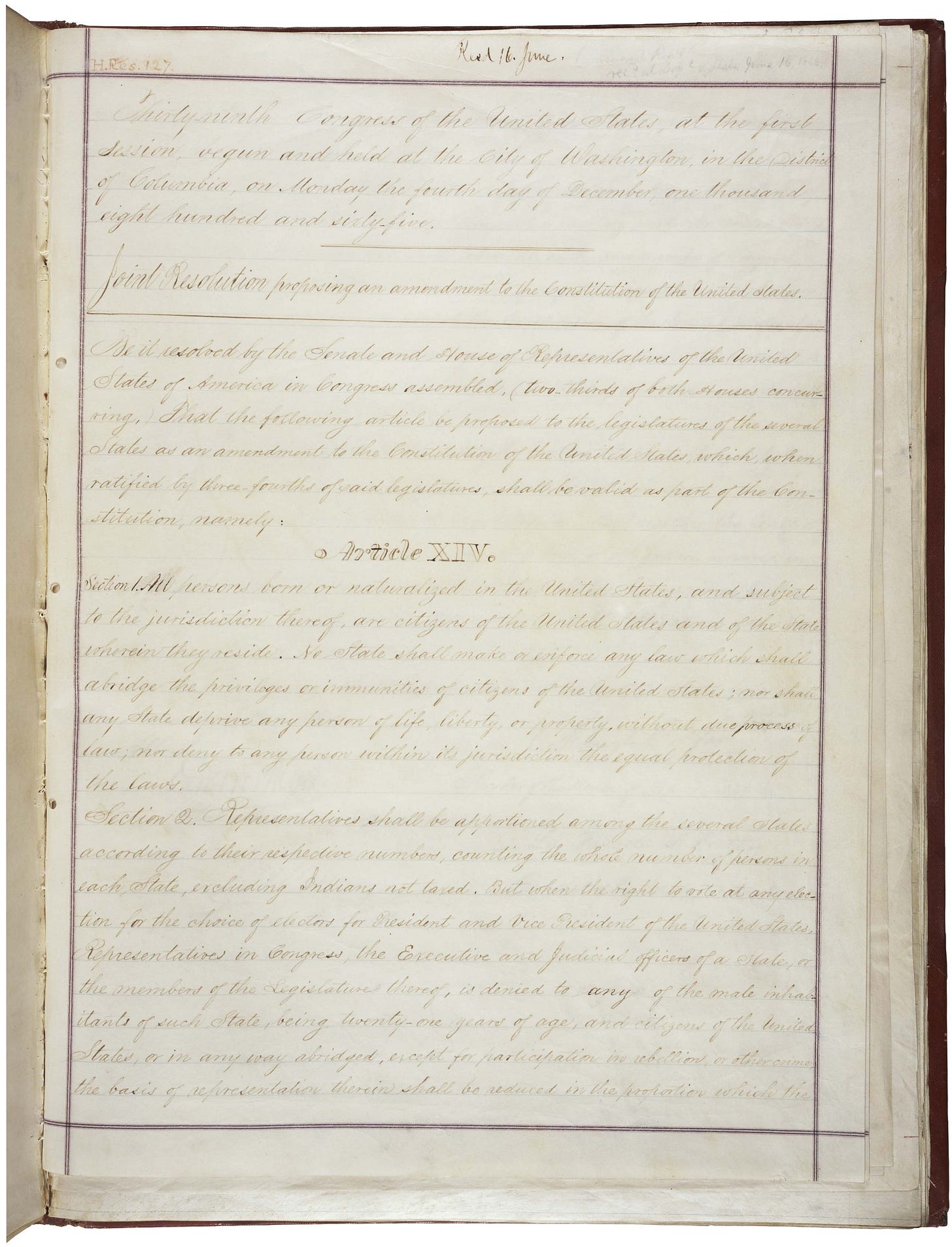

The Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, added to the Constitution after the Civil War, grants citizenship to “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” Trump’s executive order adopts a sweeping interpretation of the jurisdiction clause similar to what the Supreme Court rejected in its 1898 decision. The jurisdiction language in the Fourteenth Amendment, the majority of justices wrote, “would appear to have been to exclude, by the fewest and fittest words (besides children of members of the Indian tribes…), the two classes of cases, — children born of alien enemies in hostile occupation, and children of diplomatic representatives of a foreign state….”

Trump’s immigration policy advisors of course know this legal history. The administration’s view of the Fourteen Amendment adopts the position of two justices who dissented from the Court’s 1898 decision. The dissenters claimed that children did not obtain citizenship if their parents’ “residence was merely temporary, either in fact or in point of law.”

Yesterday’s executive order is meant to start a long legal battle that ultimately forces the Supreme Court to revisit Wong Kim Ark’s case. Trump is hoping that a new batch of justices will result in a new interpretation of the constitutional guarantee that generations have relied on. Within hours of Trump signing the order, the ACLU sued Trump on behalf of multiple community organizations around the country. [January 21 Update: The day after Trump signed the executive order, eighteen states and two cities jointly filed a separate lawsuit while four other states filed a third lawsuit.]

January 23, 2025, 3:10 pm Eastern - A federal judge in Seattle temporarily blocked the federal government from implementing Trump's birthright citizenship executive order. In a short order, Judge John Coughenour explained that Washington and the three states that joined it in the lawsuit are likely to show that the Trump administration's attempt to narrow over a century's worth of citizenship law violates the Fourteenth Amendment and the Immigration and Nationality Act. The states "face irreparable injury" if they "cannot treat birthright citizens as precisely that--citizens."